|

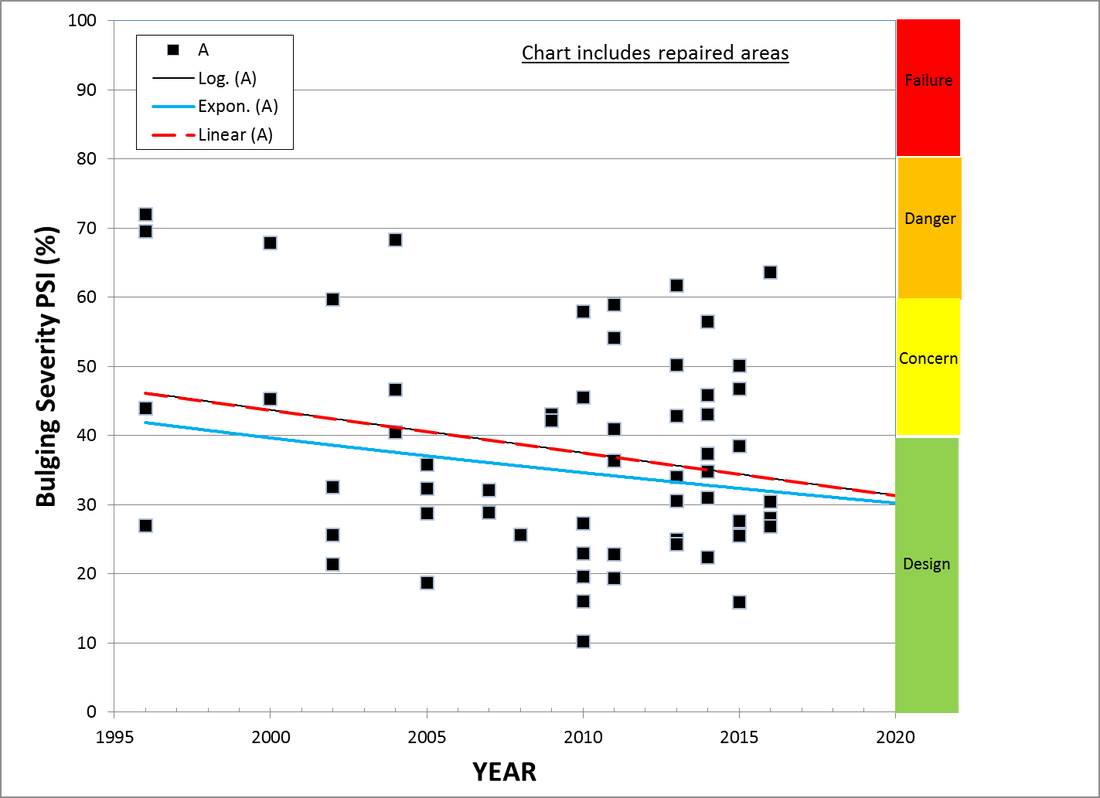

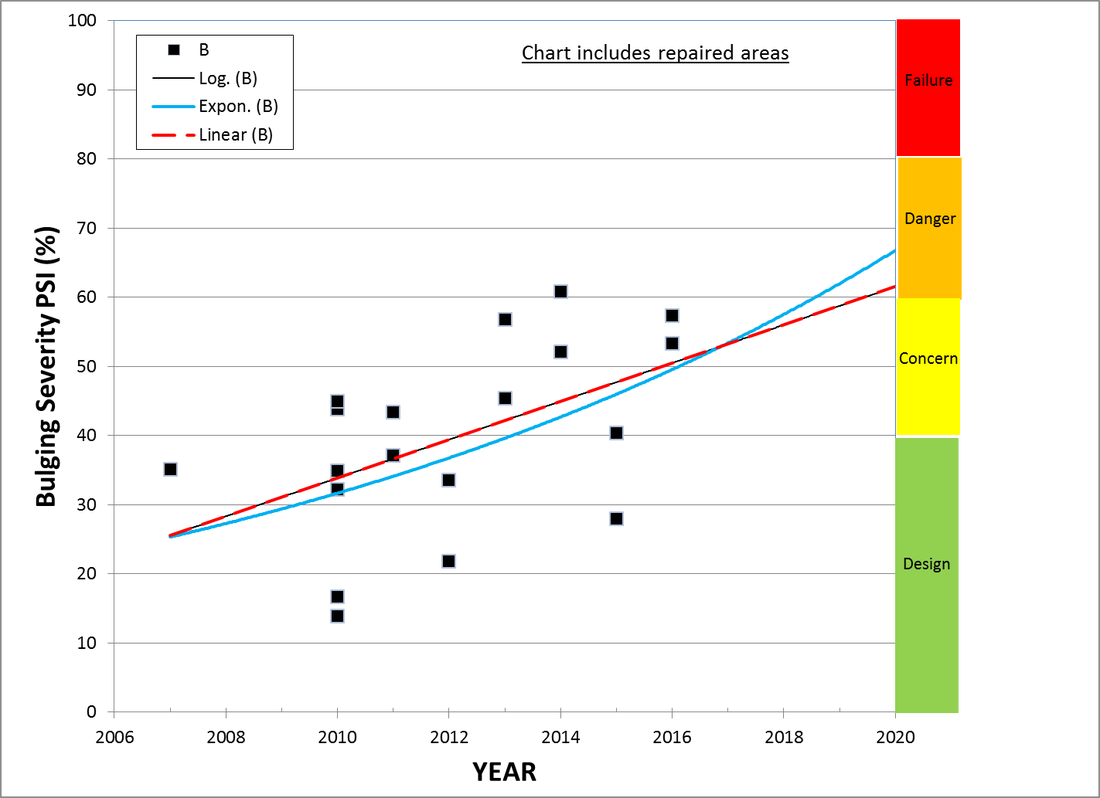

This is the most common question that I am frequently asked at conferences and seminars. To help answer this question, let’s first look at 2.1.3(e) of API 579-1/ASME FFS-1 of 2007 that says: “Remaining Life Evaluation: An estimate of the remaining life or limiting flaw size should be made for establishing an inspection interval. The remaining life is established using the FFS assessment procedures with an estimate of future damage. The remaining life can be used in conjunction with an inspection code to establish an inspection interval.” Therefore, from a fitness-for-service standpoint, “remaining life” is a calculated period used to guide the inspection of a specific damage type at a given location using an estimated rate of future damage. In a coke drum, this could mean: How long will it take a detected crack to go through-wall? Or when will a bulge reach critical size? Typically, the above question on coke drum life is intended to mean something totally different: when do we need to replace our drums? Now that we have the terminology straight, drum replacement decisions are often more dictated by regulatory climate, maintenance costs, and management confidence than by mechanical integrity. For example, jurisdictional intolerance to leaks and fear from unplanned shutdowns are common causes for replacement of drums that are mostly in excellent condition. As far as structural failures, while propensity to damage is an inevitable part of drum operation, recent advances in assessment and repair techniques have made it possible for drums to operate reliably for decades. Making preemptive decisions that prevent incipient failures from causing unplanned shutdowns has redefined the term “coke drum life”. The two graphs below show bulging severity for two sets of coke drums that process the same crude using the same operating practices at the same plant. Figures 1 and 2 belong to the older set and newer set, respectively. In both figures, the abscissa (x-axis) is time in years and the ordinate (y-axis) is the maximum severity of bulging measured using the Plastic Strain Index (PSI)TM which is the ratio of plastic strain to local failure limit in a percentage form. The graphs show that bulging severity in the older set has been decreasing with time while that in the newer set has been increasing. The only difference between the two sets is that bulging in the older set had been assessed using PSI and maximum severity locations, as determined from bulging assessment, had been mitigated using long-term bulge repairs. The unprecedented reversal of deterioration trend in the older set of drums and the stoppage of observed cracking has not only resulted in the cancellation of drum replacement plans but also prompted the plant to contemplate increasing the interval between turnarounds from three to four years. In summary, coke drums do not have a fixed end of life and do not need to be replaced by a given date. The use of advanced assessment and repair methods has made replacement a choice rather than a necessity. Figure 1 Figure 2

0 Comments

|

AuthorMahmod Samman, Ph.D., P.E., Fellow ASME ArchivesCategories |

Houston Engineering Solutions LLC

11757 Katy Freeway, Suite 1300, Houston, TX 77079, USA

Phone: +1 (832)838-4894

Web: www.HESengineers.com

Copyright © 2012 Houston Engineering Solutions, LLC All rights reserved

Phone: +1 (832)838-4894

Web: www.HESengineers.com

Copyright © 2012 Houston Engineering Solutions, LLC All rights reserved

RSS Feed

RSS Feed